The Ten Year Lunch

The origins of the Round Table, like much of its history, are shrouded in legend. This much is known: on a summer day in 1919, a press agent named John Peter Toohey invited Alexander Woollcott, the drama critic of The New York Times, to lunch at the Algonquin. Toohey, annoyed at The New York Times drama critic Alexander Woollcott for refusing to plug one of Toohey's clients in his column, organized a luncheon supposedly to welcome Woollcott back from World War I, where he had been a correspondent for Stars and Stripes. Instead Toohey used the occasion to poke fun at Woollcott on a number of fronts.

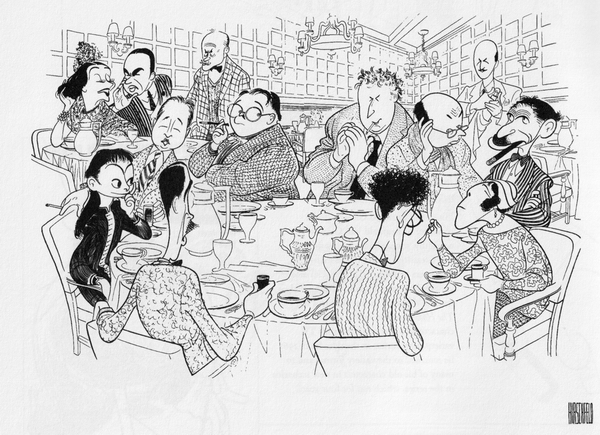

Toohey had invited the city's drama critics and editors, a group that numbered in the several dozens and included most of the men and women who would become members of the Round Table. Woollcott's enjoyment of the joke and the success of the event prompted Toohey to suggest that the group in attendance meet at the Algonquin each day for lunch.

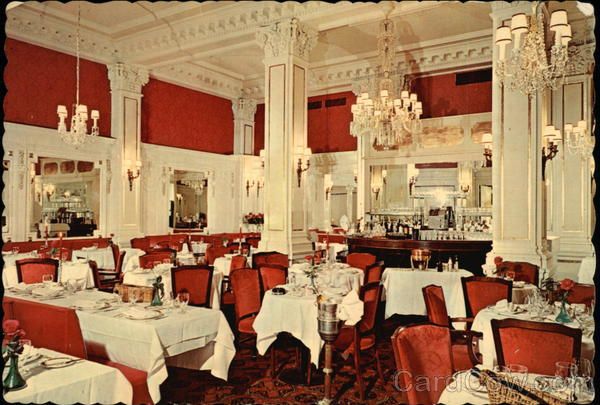

What seems clear is that the principals had no sense that they were establishing anything. They simply began to meet every day at one o'clock for lunch—because they worked nearby, because they worked in the same fields (media, public relations, performing arts), because they were young and vaguely ambitious and satisfied with each other's company. They met at first at the long table in the Pergola Room. Soon the hotel's manager, Frank Case, moved them to a round table in the Rose Room, not only because they needed the space, but because their presence drew a crowd. Eventually, Case blocked off the room with a velvet rope to hold back gaping lunch-hour star watchers; by 1928, when the members' achievements had made them famous, Case moved them back to the more private Pergola Room.